The science of soap

How soap and water combat coronavirus

May 21, 2020

Recently, hand washing has become a much-publicized defense against coronavirus and soap is the weapon of choice.

Perhaps you can still hear your mother's voice as you walked through the kitchen door, sat down to a meal or came out of the bathroom, "Did you wash your hands?"

Have you ever wondered how soap combats germs and dirt or why it works so well?

Soap can be traced back to around 2800 B.C. Archeologists discovered Babylonian clay tablets inscribed with a soap recipe. The Bible records the cleansing routine of the temple priests using water infused with ashes and animal fat from their burnt offerings.

Also, bars of soap were unearthed in the excavation of Pompeii, which was buried by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 78 A.D.

It's even possible that your great-grandmother helped make soap for her family's bathing and household duties.

Traditionally wood ash, an early form of sodium hydroxide, was soaked in water and mixed with lard, tallow or olive oil and poured into a mold. A chemical process called saponification takes place and the mixture changes into soap.

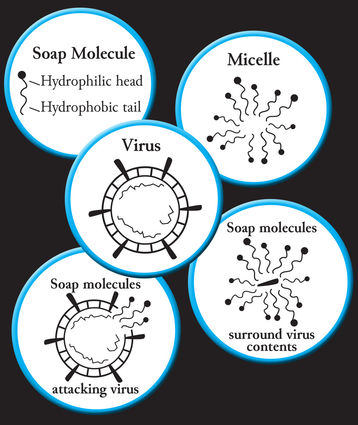

Molecules in soap are unique because of their duel bonding ability. These pin-head shaped molecules have a hydrophilic head and a hydrophobic tail. This means the head is soluble in water while the tail is attracted to lipids, fats.

When water is added to soap and lathered, these molecules cluster into what is called a micelle, the heads point outward and the tails pull together. These micelles glide over the skin's surface and pry off other molecules, such as germs, grease and dirt.

Many germs, including coronaviruses, are wrapped in a lipid membrane. Inside are the proteins that allow the virus to infect other cells.

Soap molecules attack germs by using the fat-seeking tails to rupture the membrane causing the contents to spill out, rendering the virus useless, and the water-loving head bonds with the water and rinse it away.

This soapy safeguard prevents germs from having a chance to enter your body. Modern day hand sanitizers are a good alternative, but soap and water are still the first-hand recommendation.

The surface layer of skin is rough, providing many areas for germs to take hold, especially on your hands. When germs on the hand come in contact with the face, particularly the eyes, nose and mouth, they gain an internal foothold.

One way to stop the invasion of germs is to wash your hands thoroughly and frequently. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends these five steps to washing your hands:

1. Wet hands with clean, running water (warm or cold), turn off the tap and apply soap.

2. Lather hands by rubbing them together with the soap. Lather the backs of your hands, between your fingers and under your nails.

3. Scrub hands for at least 20 seconds. Need a timer? Hum the "Happy Birthday" song from beginning to end twice.

4. Rinse hands well under clean, running water.

5. Dry your hands using a clean towel or air dry them.

The Babylonians, Pompeii's ruins and even your own household ancestors may seem like ancient history. Yet soap's recipe hasn't changed much in thousands of years or lost its ability to be an effective deterrent, even in this current crisis.

Reader Comments(0)